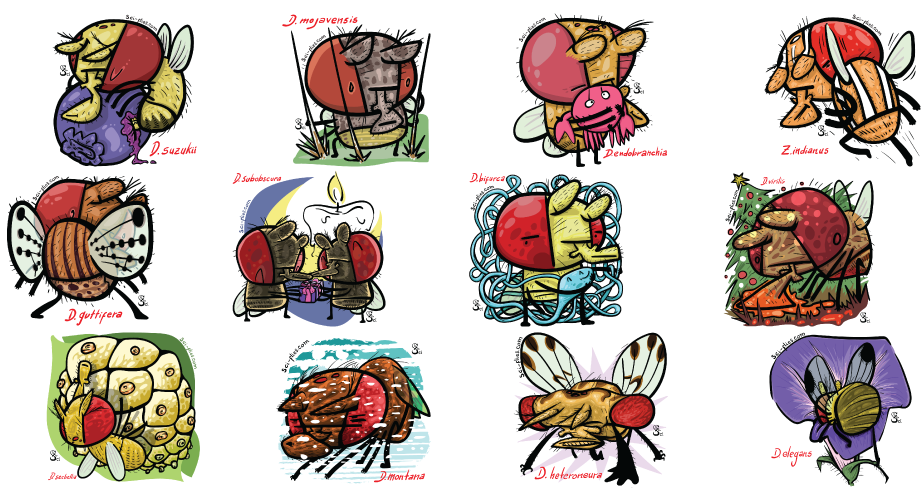

Drosophila flies, the more the merrier

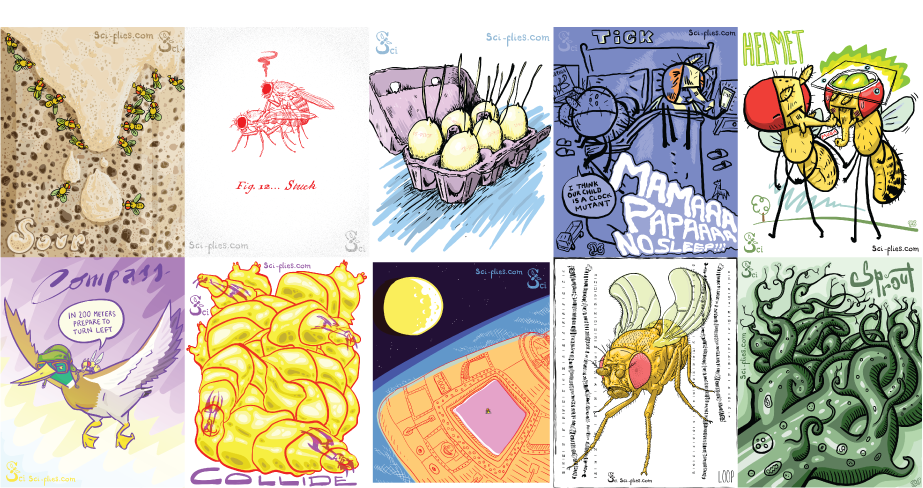

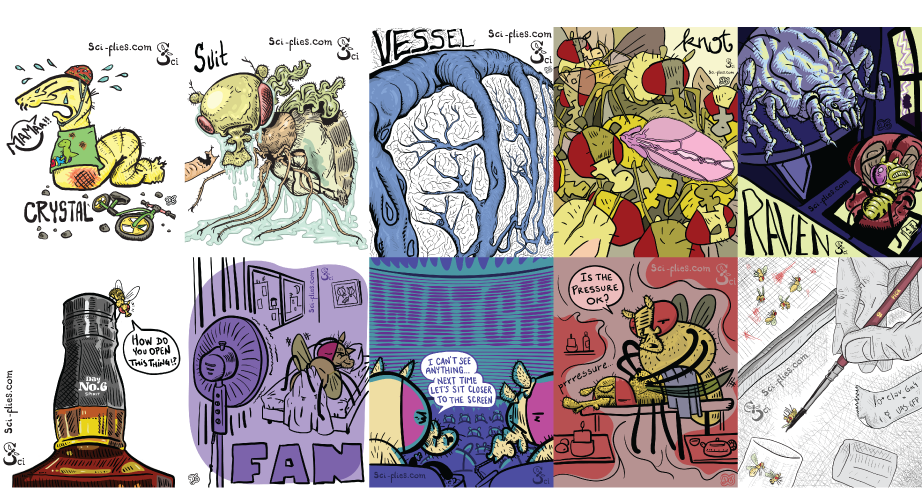

Advent calendar 2021 - Part II

One of the challenges of making this calendar was finding something interesting and simple from each of the species. Don’t get me wrong, all the species we chose are interesting in one way or another, but it is not always easy to summarize it in 3-4 Tweets of 280 characters. Twitter is quite a literary genre on itself: concise and resonant like a Haiku, and expeditious and provocative like a tabloid newspaper gazette. Will I ever master this infamous and alluring modern art?

In this second part of the calendar you will discover South American as well as Caribbean flies, ninja and impostor flies, flies of different colors and flies with different designs, some herbivorous flies and others that eat hallucinogenic mushrooms. All that and much more. I hope you enjoy!

DAY 13. Drosophila buzzatii

On this 13th Day of our Advent Calendar meet Drosophila buzzatii, the South American flies!

D. buzzatii is a cluster of seven species endemic to South America. They feed and breed on prickly pear cacti.

One of these species, D. buzzatii, spread to the “Old World”, and during the 30s it traveled from Argentina to Australia.

How did that happen?

As is the case for many invasive species, D. buzzatii most likely spread thanks to human intervention, probably being carried in their host cactus that were transported to new regions as botanical curiosities.

You can find the link to the scientific paper here:

Arguably, there are other Drosophila species that are way more interesting than D. buzzatti, but I liked the idea of featuring an argentinean species.

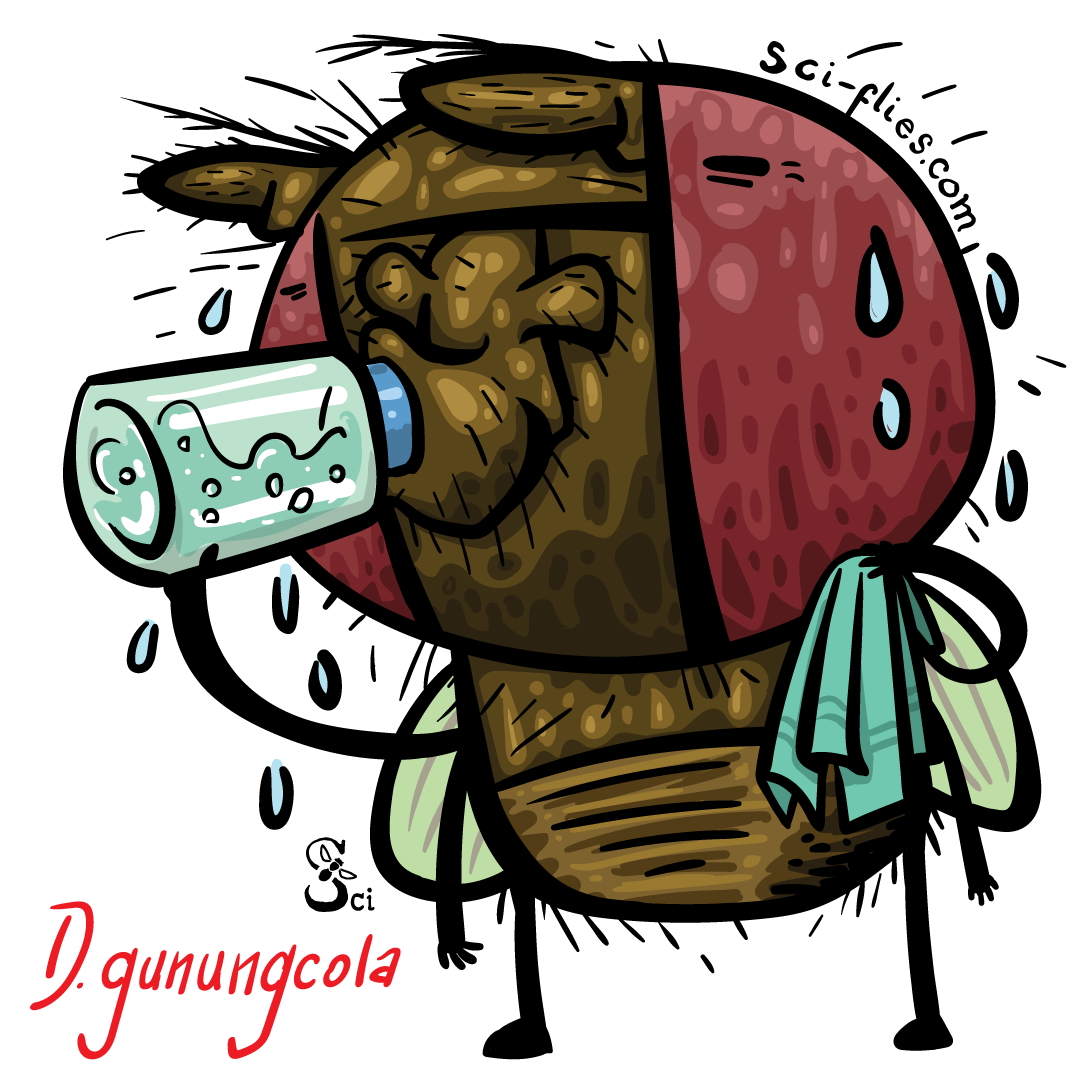

DAY 14. Drosophila gunungcola

On this 14th Day of our Advent Calendar meet Drosophila guguncula, the fly stuck in the moment!

These flies mate for more than an hour on average, and they can even go up to two hours. That’s a lot!

D. guguncula and D.elegans are sibling species. Both species have many characteristics in common but a quite visible difference: D. elegans males have a spot in their wings, while D. gunungcola male don’t.

Why is that important?

Species of flies that have male spots in their wings also exhibit a conspicuous wing display behavior during courtship, when males face females and repeatedly wave their wings and shake their bodies.

These two traits, wing spots and wing display behavior, are actually genetically separable, meaning that the genetic basis of both characteristics are not physically or functionally connected.

You can find the links to the scientific papers here:

This species was a bit difficult to introduce. Clearly the more interesting aspect of their biology is the fact that they mate for a very long time… like, a lot! The problem was, I couldn’t find anything to add about it! I couldn’t find any research where they study the physiological basis of those long mating sessions. Or even what’s the benefit of mating for so long!

In the end, I just briefly mentioned it and focused on another aspect of D. guguncula’s biology, the difference in wing pigmentation with its sister species, D. elegans, and what could be the function of the spots on the wings of males.

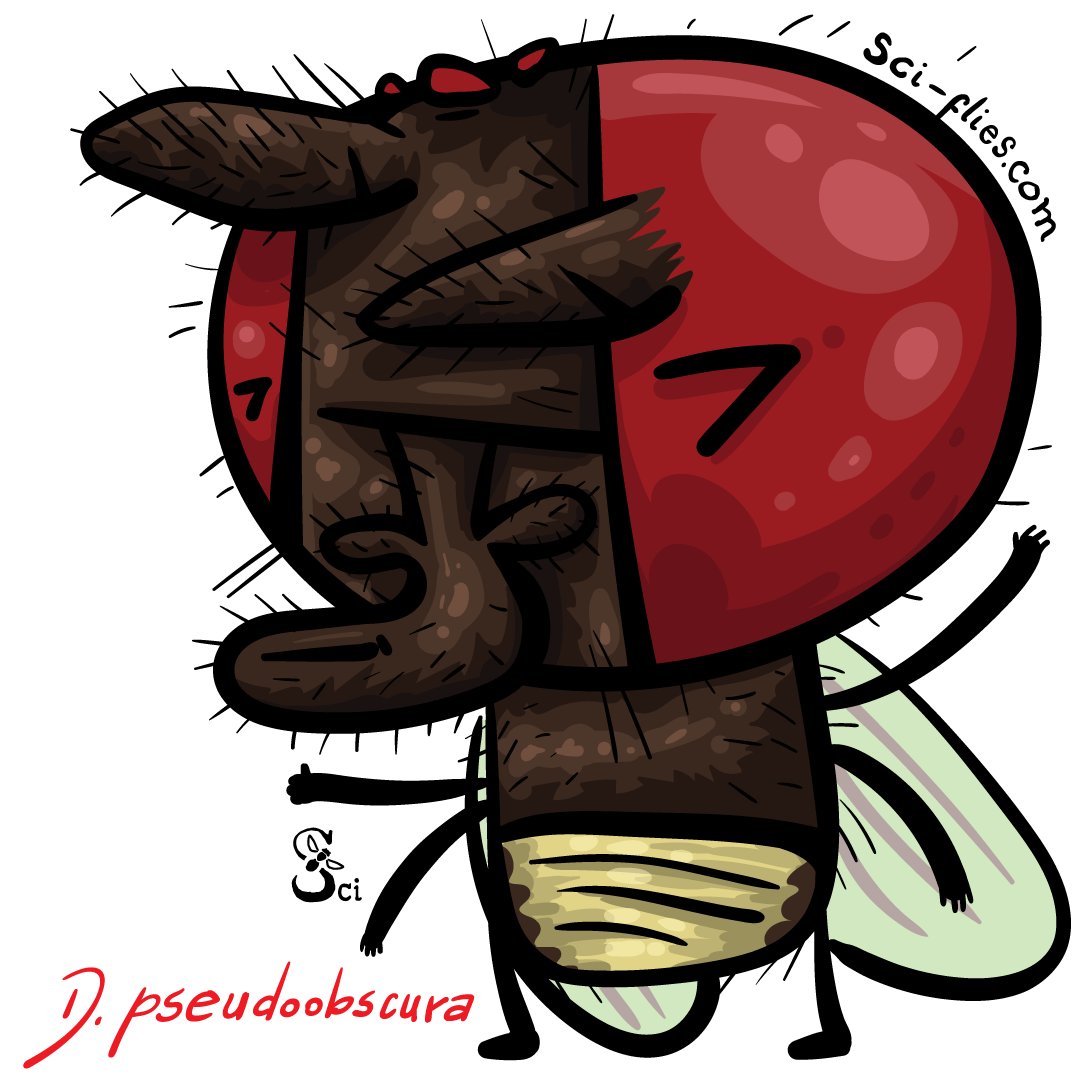

DAY 15. drosophila pseudoobscura

On this 15th Day of our Advent Calendar meet Drosophila pseudoobscura!

D. pseudoobscura has been a model species for evolutionary studies for over 80 years. One important contribution of D. pseudoobscura was the study of sex-ratio.

In natural populations, there is a condition in males called sex ratio (SR) that leads to all the progeny being female. In this condition, the X chromosome prevents the maturation of the Y-bearing sperm in males. As a consequence, this male transmits this “selfish” chromosome to all of his offspring, and all of them are females.

You can find the links to the scientific papers here:

This was another difficult species. Of course I had to talk about D. pseudoscura, one of the most important species in evolutionary studies, but I didn’t know what to focus on! I found this research on the sex-ratio,found it interesting, and decided to focus on that.

Day 16. Drosophila prolongata

On this 16th Day of our Advent Calendar meet Drosophila prolongata, the ninja fly!

Unlike most Drosophila species, D. prolongata males are bigger than females. Also, males have enlarged forelegs, which they use to vibrate the female body during courtship. This act increases the chances that the female accepts the male, but it also raises the risk of other males pursuing the same female. In the presence of rivals, males change their “leg vibration” for a “rubbing” behavior, which is less vulnerable to interference by rival males.

You can find the links to the scientific papers here:

Check out this video!

If you have time, do check the videos. They are so amazing!

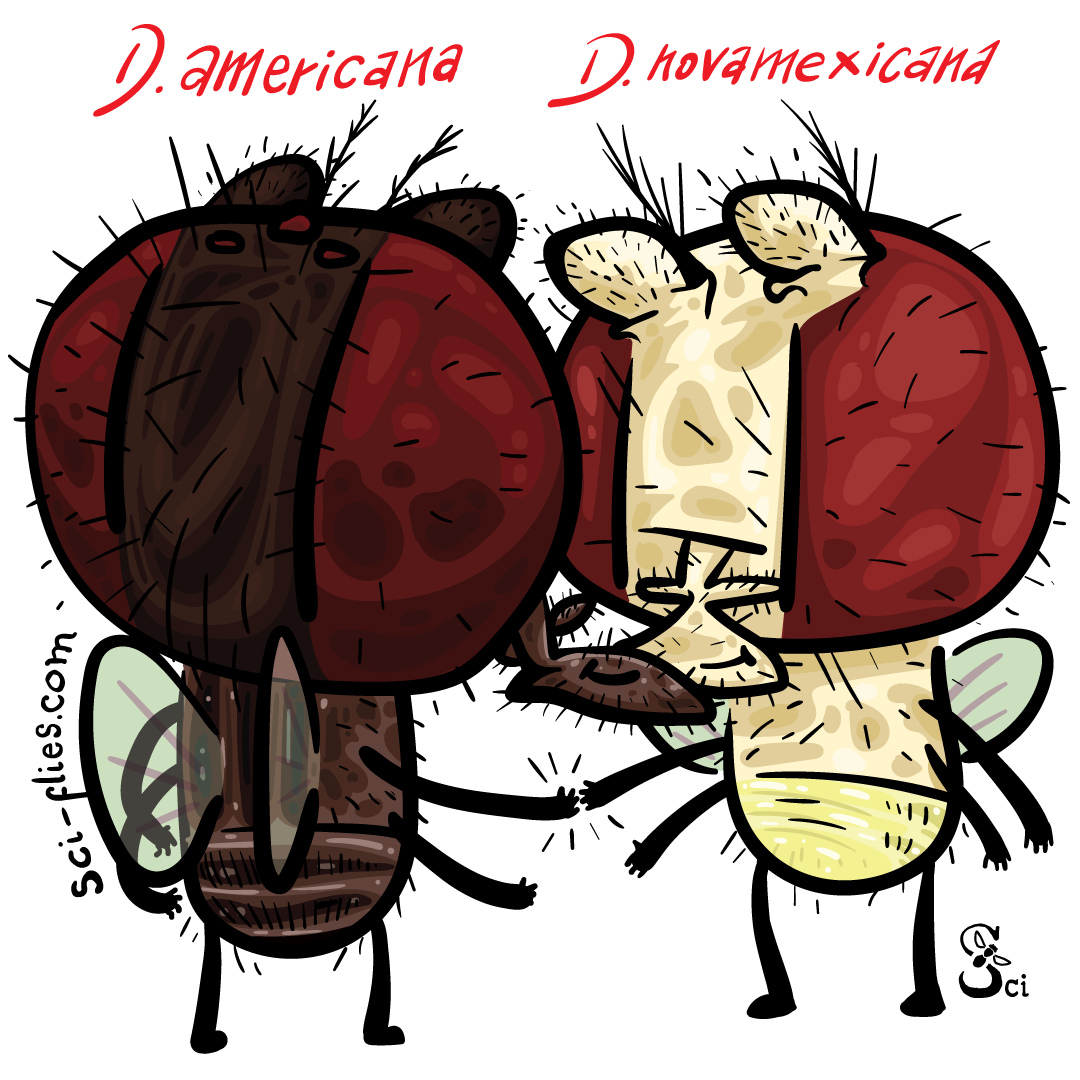

Day 17. Drosophila americana

On this 17th Day of our Advent Calendar meet Drosophila americana.

D. americana is endemic to North America and has two populations, one darker living in the East and one lighter or yellowish, in the West. A closely related species, Drosophila novamexicana, has an even lighter color.

Two genes important for pigmentation, ebony and tan, have different alleles, some of which give lighter flies and some other, darker flies. These differences could be partially responsible for the natural variation in body color in these species.

Geographical differences in environmental factors (e.g., precipitation and moisture variables) correlate with species variation in pigmentation and desiccation resistance, pointing to some interesting potential agents of natural selection.

You can find the links to the scientific papers here:

There are some very nice photos that show the gradient of pigmentation tones of this group of species. I had a small space for drawing, so it was difficult to fully represent this variety. But I liked the idea of showing both ends greeting each other like friends.

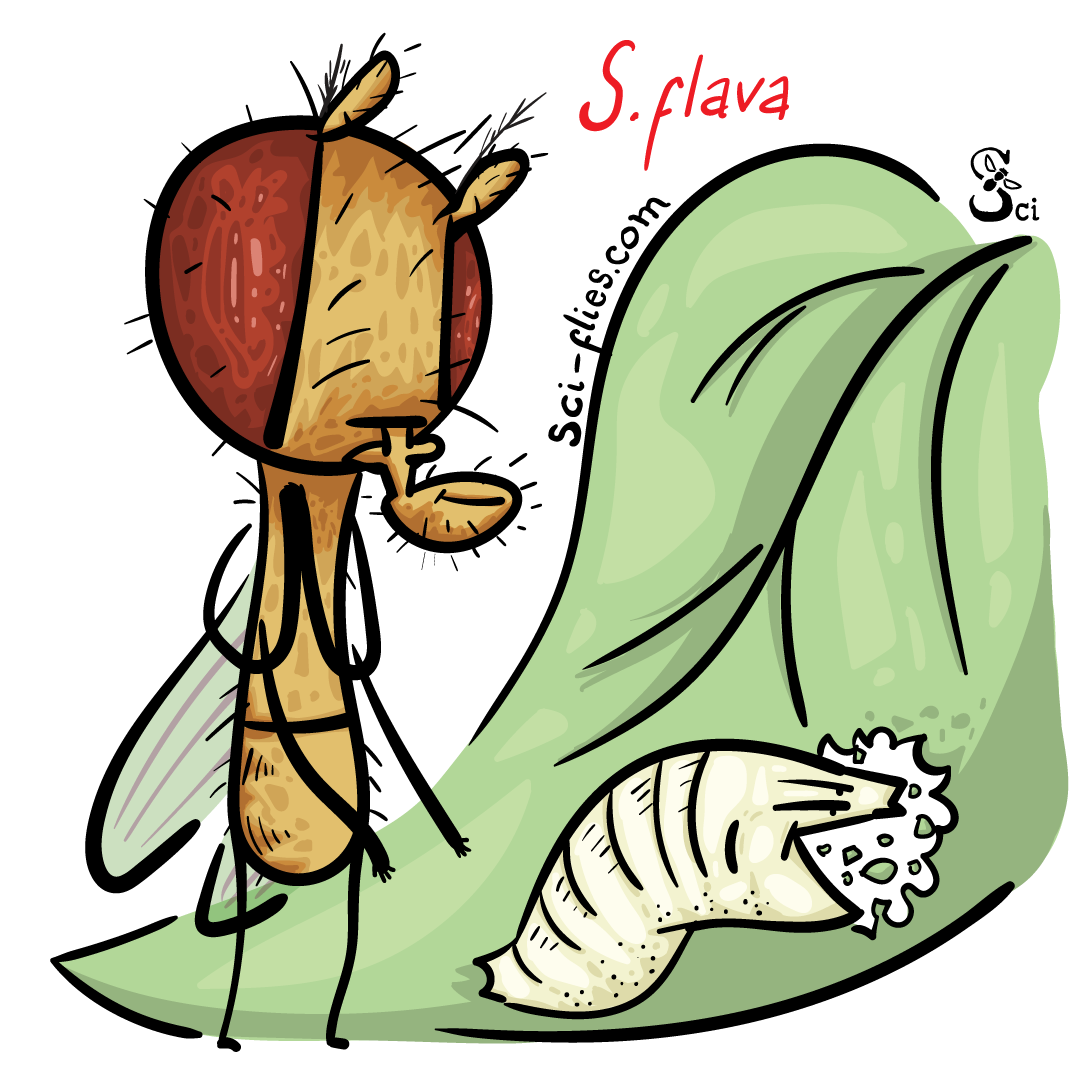

DAY 18. scaptomyza flava

On this 18th Day of our Advent Calendar meet Scaptomyza flava, a leaf miner fly!

S. flava is one of the few herbivorous species in the Drosophilidae family. Females lay eggs, and later the larvae feed on the leaves of the mustard plants, including the famous Arabidopsis thaliana.

These flies have lost several receptors that detect yeast odors, and as a consequence S. flava, unlike most Drosophila flies, is not attracted to yeast. Instead, S. flava flies have gained several receptors that allow them to detect important leaf odors. Some of such odors are isothiocyanates, which provide the plant a defense mechanism towards pathogen attacks.

You can find the links to the scientific papers here:

When I read about this species and saw its photo, this image immediately came to mind. Adult flies are more stylized than D. melanogaster and I love to draw the larvae as if they were little babies or toddlers.

day 19. Drosophila neotestacea

On this 19th Day of our Advent Calendar meet Drosophila neotestacea, the psychedelic fly!

Drosophila neotestacea is another Northamerican fly, with a peculiar taste for psychoactive mushrooms (Fly Agaric or Amanita muscaria, used in shamanic rituales).

These flies are commonly infected by a parasitic nematode. Infections are very serious, causing female sterility, and reducing adult survival and male mating success.

Luckily, flies acquired a defense mechanism against these parasites. D. neotestacea hosts a symbiont bacteria that protects her against the sterilizing effects of the nematode.

How do they do that?

The bacteria release a toxin that attacks the ribosomal RNA of the parasitic nematode, and in doing so, it provides a protective mechanism against disease.

You can find the links to the scientific papers here:

Drosophila neotestacea feeds on fungi that have hallucinogenic effects for humans. Although they are immune to the substances that fungi produce, I liked the idea of drawing them on a psychedelic trip.

day 20.Drosophila busckii

On this 20th Day of our Advent Calendar meet Drosophila busckii!

Drosophila busckii is a fly native to North America from the subgenus Dorsilopha, in which only 4 species have been recorded so far. It is almost a universal human commensal, feeding on many different vegetables, animal excrement, and meat.

These flies have dark brown stripes in the yellow thorax, a pattern named “the trident” that is also present in some populations of D. melanogaster. The shape of the trident is a by-product of the patterning of flight muscle attachment site patterning. The protein Stripe determines where the flight muscles attach and it delimits the shape of the trident by repressing the expression of multiple genes involved in pigmentation.

You can find the links to the scientific papers here:

A way to show the thorax and abdomen of this beautiful fly.

day 21. drosophila innubila

On this 21th Day of our Advent Calendar meet Drosophila innubila, the fly living in the high-elevation woodlands!

D. innubila feeds on mushrooms and lives in the high-elevation woodlands in the mountains of the southern USA and Mexico.

These flies are frequently infected by a specific DNA virus, which reduces the life expectancy and fecundity of flies.

A more virulent strain of this virus has mutated and evolved several times since they started infecting Drosophila flies. Now, this strain can suppress more effectively the fly immune system.

Meanwhile, genes of the Toll pathway, involved in the immune response against fungi, viruses, and extracellular parasites, are also evolving rapidly in D. innubila.

You can find the links to the scientific papers here:

I really enjoyed researching this species. I like to learn about viruses, and coevolution of pathogens and hosts.

day 22. drosophila dunni

On this 22nd day of our Advent Calendar meet Drosophila dunni, the Caribbean flies!

The Dunni group are Drosophila species from the Caribbean islands that show a striking variation in pigmentation, following the different climates across the islands.

The gene yellow plays an important role in the evolution of these divergent pigmentation patterns.

When did the pigmentation patterns start to diverge?

There were two major rounds of diversification. The first occurred 1.6–2.6 million years ago and separated three major lineages, one in Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands, a second in the northern Lesser Antilles and Barbados, and a third in St. Vincent and Grenada. The second round of diversification occurred in the last 96,000 years in the northern Lesser Antilles and Barbados.

You can find the links to the scientific papers here:

I only found images of the abdomens of the Antillean fly species. I’m not sure their colors are actually the ones I chose here. But they were pretty.

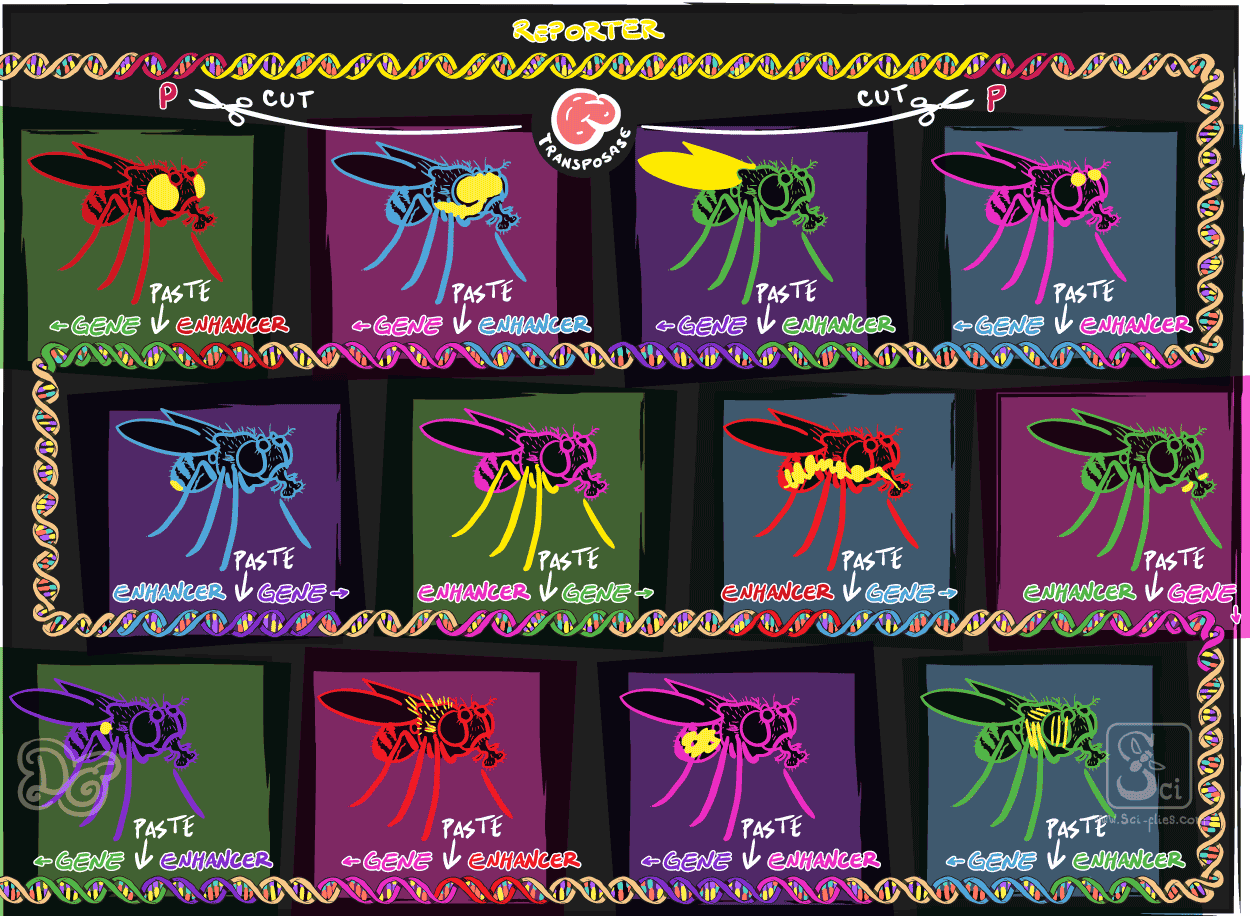

day 23. drosophila simulans

In 1919, Sturtevant published a paper describing “A New Species Closely Resembling Drosophila Melanogaster”.

Who was this mysterious fly that simulated to be D. melanogaster and had fooled Morgan and his disciples? It was Drosophila simulans.

Although both species can cross and produce sterile progeny, they generally don’t mate because they don’t like to court each other. D. melanogaster females produce a pheromone that promotes courtship in D. melanogaster males but prevents courtship in D. simulans males. Males of both species detect this pheromone similarly, but the brain processes differently, leading to opposite behaviors (courtship YES vs courtship NO) in these two sister species.

In the last two decades, many genetic tools have been incorporated into D. simulans, from the expression of fluorescent proteins, neuronal activity reporters, driver lines, lines to do CRISPR, to, very recently, chromosome balancers! These are very exciting times for researchers working with D. simulans!

You can find the links to the scientific papers here:

I knew from the beginning that Drosophila simulans had to be on the calendar. This is the second most famous species in the genus (the first one being, of course, Drosophila melanogaster). I enjoyed reading about the first report of this species by Sturvetant, and how it was initially mistaken for one more melanogaster in the laboratory of T.H.Morgan (yes, the same Morgan of the genetic basis of heredity). Sturvetant was the first one to record more than 240 Drosophila species.

I love that the same people who were studying how genes carry the genetic information in D. melanogaster, also paid attention to the biodiversity of this wonderful genus. Perhaps they understood that the key to really understanding how genes determine our physiology was to ultimately study the evolutionary processes that lead to the natural selection of some characters?

I told Diego I wanted to play with the idea of D. simulans pretending to be D. melanogaster and I found the painting by René Magritte (Ceci n’est pas une pipe) very appropriate to illustrate this idea.

day 24. drosophila mercatorum

On this 24th Day of our Advent Calendar meet Drosophila mercatorum, a facultative parthenogenic fly!

Parthenogenesis is a form of asexual reproduction where an unfertilized egg gives rise to an embryo.

D. mercatorum is a facultative parthenogenic species, meaning that, while it mostly reproduces sexually, under certain circumstances it can reproduce via parthenogenesis.

Facultative parthenogenesis may be an adaptive reproductive strategy in Drosophila when a few founders colonize a new place, consistent with models of geographical parthenogenesis.

You can find the links to the scientific papers here:

When someone on Twitter suggested introducing a parthenogenetic species, Diego and I immediately agreed that it should be for the last door, the 24th.

I hope no one is offended, but, in the world of science, the Virgin Mary is known as the most famous case of parthenogenesis in humans! I think that, in a way, it is the best scientifically based solution to explain the miracle of the immaculate conception.

This is the end of our Advent Calendar. We hope that you liked it, learned something, and hopefully fell in love with the beautiful biodiversity of the Drosophila genus.

See you soon with more original content for you!